In the most basic terms, Hypertrophy refers to an increase in the size of a…

The Skill of Acquiring Skills

They know enough who know how to learn

~Henry Adams

Passive vs. Proactive

We all have a choice to make: Will you choose to take responsibility for the process of acquiring new skills, or will you wait for someone to bestow the skill upon you (magic fairy dust)? Choosing to be proactive empowers you. This can be scary. Once you realize that you are empowered, you also realize that no one can do it for you and that you are ultimately responsible for your own success or failure. The reality is, it’s already your responsibility, whether you chose to acknowledge it or not. In this article, I first distinguish between passive and proactive learners, and introduce key considerations that will help you become more proactive in your own training.

Passive learners:

- Avoid taking responsibility for their own progress.

- Don’t spend extra time working on developing skills.

- Go through the motions at training and don’t pursue a deeper understanding of the sport.

- Wait for a magic cue that will make everything better.

- Blame other people for their shortcomings.

- Typically will not perform to potential.

Proactive learners:

- Take ownership of the development process. They recognize that they are responsible for their own results, and they like it that way.

- Honestly assess their own strengths and weakness.

- Set aside time to practice the skills that require extra work.

- Engage in deep practice. They focus on what they do and dedicate significant mental energy to feeling and understanding whatever it is they are practicing.

- Realize that there is no magic cue or pill.

- Take ownership of their training, which increases the likelihood that they will maximize their potential.

Factors that affect learning

Agglomeration

Refers to the tendency of high-skill performers to develop in clusters. Several factors that are the primary contributors to this phenomenon are:

- We mimic the behaviors of the people around us. (Particularly, training habits and proper movement)

- The culture of our community often becomes our norm. (This can be good or bad.)

- High performers tend to want to train in the company of other high performers.

We all learn in different ways, but some of the most common and readily available methods are:

- Visual (watching how others train and move)

- Auditory (listening to an explanation of how to perform a skill or task)

- Physical (practicing the movement)

- Reading (almost anything that you want to learn has been explained in writing)

The Process

Analyze the task

Start with the big picture: Determine what you are trying to accomplish. Next, identify the skills that will get you there. For most athletes, this will mean identifying which skills score the most points, improve efficiency, and contribute most significantly towards their desired outcomes. A good way to start is by breaking down and analyzing past competitions or similar events. An experienced coach or training partner can also be very helpful in identifying the most important uses of your time and energy.

There will be a lot of “noise,” and a lot of opportunities to spend disproportionate amounts of time and energy on tasks that don’t warrant the attention. The flashy stuff isn’t always the important stuff. Avoiding these distractions gives you a significant advantage over those who haven’t taken the time to assess the task and tease out the truly important skills.

Do the math

1. Which skills occurred most frequently?

2. Which skills were deal breakers? (Skills that will eliminate you if you lack them, regardless of your strength in other skills)

3. Which skills have the highest transfer to other skills?

Don’t trust your first impulse or emotional response. Dig in, break the events down by the numbers, and identify the truly important skills.

Create a Plan

Once you have identified the most important skills, create a plan to address them in as effective a manner as possible. Keep skill practice sessions short and highly focused. When learning a skill, do it in a fresh state and early in the training session. After you have mastered the skill in a stress-free and rested state, then it’s time to turn up the stress. Practice the skill mixed with other skills, increase speed, increase resistance, and do it in a state of fatigue.

It is important to decrease stress when learning a new skill. It is equally important to practice skills under stress after you have the requisite level of mastery. In the “real world” or during competition, you will probably need to be able to perform the skill in a dynamic environment and under considerable stress.

Introducing a New Skill

When practicing a new skill it is important to remove as many stressors as possible.

- Break the movement apart in to smaller, more manageable pieces

- Slow the movement down.

- Deload the movement. (Learn the movement before you add weight.)

Adding weight to a poorly executed movement is like coming home to find your house is on fire and trying to put it out with gasoline. It’s not going to help. In fact it will probably make the problem a lot worse.

Plan each training session

Effective training structures will allow you to use your time and energy in an efficient manner and will allow you to measure progress. In some situations, you will be able to isolate a single skill and focus all of your energy on developing it. In other situations, you will need to plan for development over time and account for practicing multiple skills.

Elements of structure

- Establish measures of success

- Establish a structure for work and rest

- Limit the duration of practice (to maintain focus and avoid overuse injuries)

- Identify specific drills

If you are training to develop multiple skills simultaneously, it is important to take long-term training structure into consideration.

Start Big Picture

At what point will you prioritize the skill in your training cycle? How will you maintain perishable skills once you have acquired them?

Macrocycle (An outline of your yearly training plan.)

This will ensure that you address skills progressively, create a proper blend of training stimuli, and maintain perishable skills. It’s easy to lose sight of the forest for the trees. Don’t commit unwarranted amounts of time and energy to any single component of training.

Mesocycle (Midrange training plan of 2-8 weeks)

This will allow you to focus on shorter periods of time and still adhere to the bigger plan. Focus will generally shift as you transition from one mesocycle to the next.

Microcycle (Weekly training plan)

The weekly training plan allows you to manage how the different training stimuli interact and affect each other. Looking at the microcycle (with its shorter timespan) allows you to pay more attention to detail.

Daily Plan

The way that you structure your daily training can greatly affect the stimuli. Prioritize and order your training activities in a manner that is most likely to elicit the desired adaptations and that fits into the overall plan.

Frequency

The frequency with which you practice a skill is an important factor in determining how quickly and thoroughly you master a skill.

1. Weekly: Managing the intensity and volume of your skill will determine how many times per week you practice a skill. Lower volume and intensity allow for higher frequency, which is often helpful for skill acquisition.

2. Daily: It can be helpful to practice a skill multiple times throughout the day, in small doses.

3. Intra-Training Session: You can even address a skill multiple times in a single training session. This can be accomplished by interspersing micro doses of the skill between other pieces of the training session.

Be Patient With Yourself

Developing new skills is an ongoing process and can only be compressed so much. If things are not going well, you may be best served by ceasing practice and coming back to it another day; your mind processes and organizes new skills and information while you sleep.

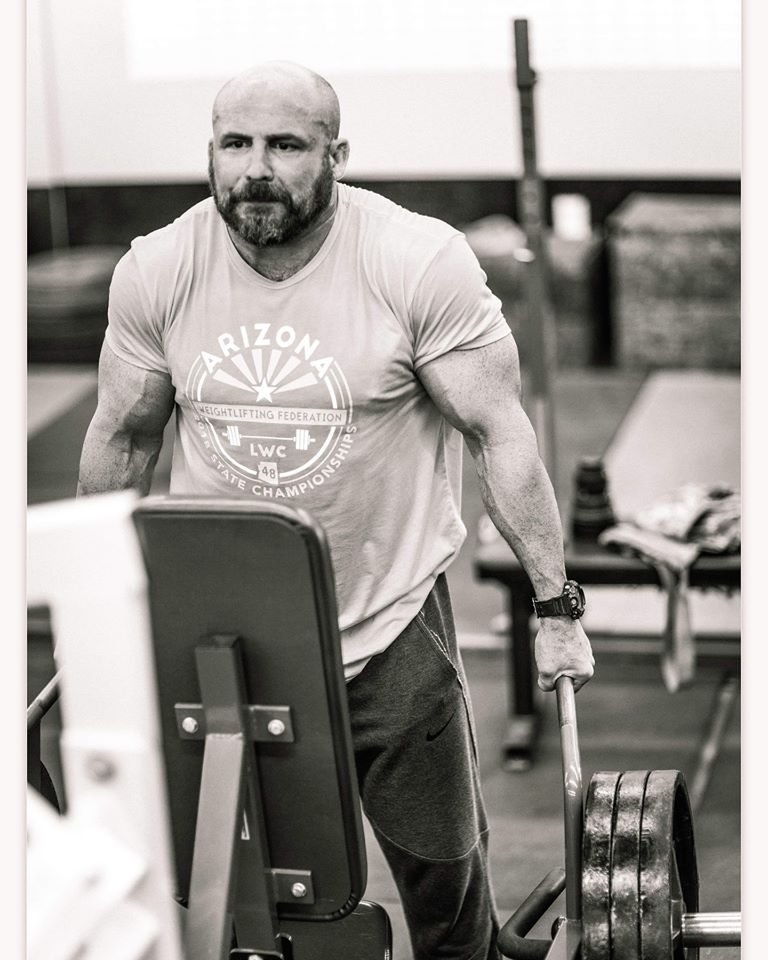

-Bachelor of Scie nce, Auburn University 1997

nce, Auburn University 1997

-Master of Education, Northern Arizona University 2005

-USA Weightlifting Club Coach 2001

-CrossFit Level 1 Instructor 2009

-USA Weightlifting National Coach 2012

-EVCF Regional Team Coach 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017

-EVCF CrossFit Games Team Coach 2014

-Masters National Record Holder: Snatch 130kg & Total 287kg (105kg 40-44)

-5 x American Masters Weightlifting Champion

-5 x American Masters – Best Lifter (2 x 35-39yrs, 3 x 40-44yrs)

-3 x Masters Nationals Weightlifting Runner-up

-President of Arizona Weightlifting Federation – LWC 48, 2016-current