In the most basic terms, Hypertrophy refers to an increase in the size of a…

Three Costly Training Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Athletes face a minefield of potential mistakes when it comes to choosing a training program. The following are several common errors made by motivated, ambitious athletes in regards to programming. These are “macro level” errors; in other words, these pitfalls occur when selecting overall program type and structure.

- Following inappropriate programming: Inappropriate in the sense that the athlete is not physically or mentally prepared for the rigors of the prescribed training. This is often the case when an athlete follows programming that was not designed for someone with their training history, physical traits, or training objectives. Two common examples of this are: 1) when an athlete immediately begins an advanced training program; or 2) when an athlete chooses to follow an elite athlete’s training program. Rarely are either of these approaches to program selection effective or sustainable.

- Combining several specialized programs: Programs for specialized athletes are not intended to be combined with other specialized programs. Think about it: when a weightlifting coach writes a program for an athlete training to be a weightlifter, that program is designed to make the athlete as strong as possible. This means that the program is going to push the athlete’s work capacity and recoverability to the limit. These types of programs are typically intended to be the sole training that an athlete undertakes. Combining multiple “standalone” programs rarely ends well.

- Attempting to “compress” the process: If you’re truly serious about your athletic development, you must accept that it will take years of consistent, highly focused training. That being the case, you can’t and shouldn’t try to do everything at once. Excessive compression is common amongst ambitious, competitive people. The problem is, we can only coax our bodies into adapting at the rate determined by our physiological and lifestyle limitations. Typically, the athletes who take this approach burn out quickly due to overtraining or lack of long-term focus and discipline.

Now that we are aware of these potential training pitfalls, how do we recognize and avoid them?

- Accept that athletic development is a long, slow, and sometimes frustrating process. The road to success is long and often owned by those willing to put in consistent, hard work over a sustained period of time. It is not unusual for an athlete to require seven or more years of training and competing in order to reach the upper limits of their competitive potential. In many sports (depending on level of competitiveness) an athlete will require three to five years to become highly competitive. It is bordering on absurd for an athlete to expect to reach a high level of competitiveness in a shorter period of time. It is important for the coach to clearly explain the type of commitment that will be required in order for the athlete to reach their desired level of competitiveness. It is also important to remember that the athlete may not reach their objective even if they do everything to the best of their ability. This is just the reality of a competitive world. These are all reasons to drive home the importance of enjoying the process. The athlete will spend the vast majority of their time in the training process and very fleeting moments in competitions. The process is what changes you; it’s where you build relationships, learn lessons and it’s where you spend most of your time. The championship is short-lived, does little to change you, and does not lead to sustained happiness. Long-term happiness is a function of your relationships, your passion for your craft, and your personal belief system. Happiness is not on the other side of achievement.

- Understand that there is no magic training program, magic supplement, or miracle cue. The closest thing to magic is surrounding yourself with people who make you better. These people will usually be growth-minded (they read and value learning). They will have a positive, team-oriented outlook on their relationships and the greater group. They train with a high degree of discipline and focus (deep practice). They enjoy the process of training and competing. It’s also always a good idea to put yourself around people who are better than you (people whose egos won’t allow this are costing themselves dearly).

- Get your programming from a coach who knows you. A significant portion of the value that a coach adds is based on their ability to observe and interact with you. A good coach knows that the program is not written in stone. Experience and a deep understanding of the process enable the coach to spot issues that need to be addressed, give immediate feedback, and make appropriate adjustments.

The biggest mistake that most people make when beginning or resuming training is doing too much—too much volume, too much intensity, and too much frequency, or some combination of these. This overly-aggressive approach to training often ends in burnout or injury, neither of which moves you closer to your objective.

When you’re starting from a sedentary state, or when you’re significantly detrained, it doesn’t take much stimulus to elicit an adaptation and to tax your ability to recover. Start slow. It is more important to be able to train consistently than it is to have one overly-challenging training session. In time, with appropriate training, the body’s tolerance for work will increase.

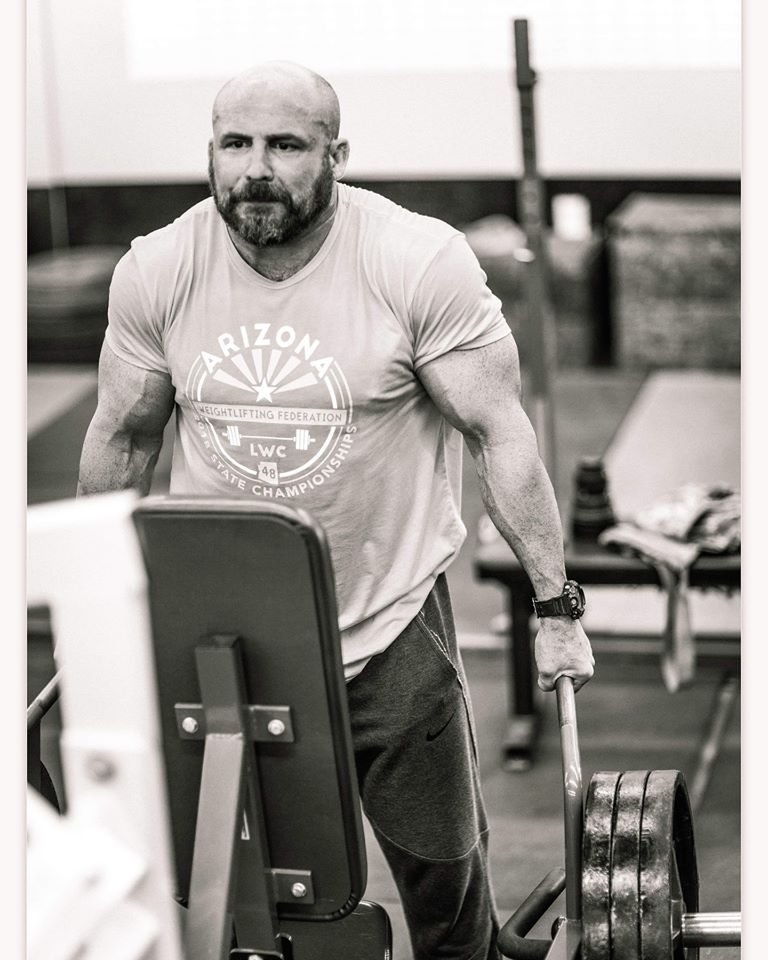

-Bachelor of Scie nce, Auburn University 1997

nce, Auburn University 1997

-Master of Education, Northern Arizona University 2005

-USA Weightlifting Club Coach 2001

-CrossFit Level 1 Instructor 2009

-USA Weightlifting National Coach 2012

-EVCF Regional Team Coach 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017

-EVCF CrossFit Games Team Coach 2014

-Masters National Record Holder: Snatch 130kg & Total 287kg (105kg 40-44)

-5 x American Masters Weightlifting Champion

-5 x American Masters – Best Lifter (2 x 35-39yrs, 3 x 40-44yrs)

-3 x Masters Nationals Weightlifting Runner-up

-President of Arizona Weightlifting Federation – LWC 48, 2016-current